Primitive Software

Primitive technology is a hobby where you make things in the wild completely from scratch using no modern tools or materials. This is the strict rule. If you want a fire- use fire sticks, an axe- pick up a stone and shape it, a hut- build one from trees, mud, rocks etc. The challenge is seeing how far you can go without modern technology.

– John Plant

Primitive software is a hobby where you make things in the hardware completely from scratch using no external tools or code. This is the strict rule. If you want a program- create it, a boot executable- pick up a chip and toggle it in, a toolchain- build one from your own assembler, linker, compiler etc. The challenge is seeing how far you can go without external software.

A quick hardware detour

People who are really serious about software should make their own hardware.

– Alan Kay

Primitive software is most pleasing when written for homemade hardware, like a computer built from steam-powered mechanical gears, fulfilling Babbage’s vision, or electromechanical relays like Zuse. To progress beyond tens of operations per second requires1 electronics: thermionic valve vacuum tubes or even faster solid-state transistors. Using DIP chips in a breadboard à la Ben Eater is more practical, and those small-scale integrated circuits are logically equivalent to ones hand wired from a few discrete transistors. But the more integrated the parts, the lesser the claim to having built the computer.

Such hardware usually implies a bespoke and very limited set of instructions to write programs in, but it doesn’t have to. RISC-V is a free and open-source Instruction Set Architecture, the core hardware specification that defines which set of instructions a computer can run. It was designed to allow the same basic instructions to run on tiny microcontrollers, giant supercomputers, and many specialized systems in between; with extensions added where needed.

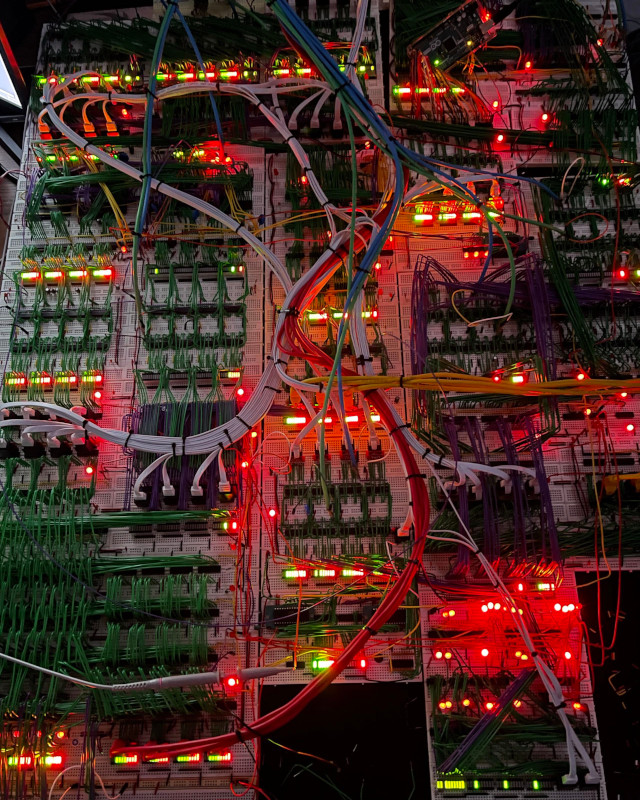

Base 32-bit RISC-V can be implemented with DIP chips for logic and parallel SRAM for memory (logically equivalent to an array of flip-flops hand wired from discrete transistors but more integrated and thus more affordable and performant). The smallest public implementation does it with 153 7400-series chips costing around $100. Toggle your program manually into an EEPROM connected to the system bus at the reset vector (i.e. the address where the computer fetches its first instruction when powered) and enjoy the program on IO hardware of your choice:

A software workaround

What is real? How do you define real?

– Morpheus, The Matrix

Breadboard computers certainly have a geeky charm, but you don’t need one to write primitive software: the recursive nature of computation implies that hardware can be turned into software and vice versa. The QEMU emulator implements RISC-V, and its virtual peripherals can mimic the simplicity of the breadboard experience. By (ab)using its 16550-compatible UART serial port to print to a terminal, ignoring the readiness checks required for most real hardware, we get about the simplest possible interface. A hex editor can enact manually toggling 40 bytes into EEPROM.bin:

37 03 00 10 93 02 80 04

23 00 53 00 93 02 90 06

23 00 53 00 93 02 10 02

23 00 53 00 93 02 A0 00

23 00 53 00 73 00 50 10

Which can then be connected at the reset vector:

qemu-system-riscv32 -M virt -nographic -device loader,file=EEPROM.bin,addr=0x80000000

Voilà, Hello, World! from software scratch. Ctrl-A x to exit. But we are not finished: a binary handed down from on high from goes against the spirit of primitive software. Time to reverse engineer!

RISC-V instruction format

What I cannot create, I do not understand.

– Richard Feynman

EEPROM.bin is shown in 10 4-byte blocks, no coincidence. RISC-V uses 32-bit instructions2, with the lowest two bits set to 1 to distinguish them from the Compressed extension’s 16-bit abbreviations. Bits [6:2] form the opcode:

| [6:5] | XX000 | XX001 | XX010 | XX011 | XX100 | XX101 | XX110 | XX111 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00 | LOAD | LOAD-FP | custom-0 | MISC-MEM | OP-IMM | AUIPC | OP-IMM-32 | reserved |

| 01 | STORE | STORE-FP | custom-1 | AMO | OP | LUI | OP-32 | reserved |

| 10 | MADD | MSUB | NMSUB | mMADD | OP-FP | OP-V | custom-2 | reserved |

| 11 | BRANCH | JALR | reserved | JAL | SYSTEM | OP-VE | custom-3 | reserved |

whose type:

| Type | Opcodes |

|---|---|

| Register-register | AMO, OP, OP-32 |

| Register‑Immediate | LOAD, LOAD-FP, MISC-MEM, OP-IMM, OP-IMM-32, JALR, SYSTEM |

| Store | STORE, STORE-FP |

| Branch | BRANCH |

| Upper immediate | AUIPC, LUI |

| Jump | JAL |

determines the format of the rest of the 32 bits:

|31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07|type

| funct7 | rs2 | rs1 | funct3 | rd | R

|11 imm 0| rs1 | funct3 | rd | I

|11 imm 5| rs2 | rs1 | funct3 |4 imm 0| S

|12|10 imm 5| rs2 | rs1 | funct3 |4 imm 1|11| B

|31 imm 12| rd | U

|20|10 imm 1|11|19 12| rd | J

An immediate first instruction

A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.

– 老子

We begin decoding EEPROM.bin by flipping the first 4 bytes from computer-friendly little endian to human-conventional big endian

0x10000337. Pretty leet, right? From its binary equivalent

0001 0000 0000 0000 0000 0011 0011 0111

we take opcode 01101, which the table above reveals as LUI: a U-type instruction. We can explain its meaning bit by bit, from the lowest to the highest:

|31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00|

|31 imm 12| rd | LUI | |

| 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

The first new field is rd, which stands for destination register. What’s a register? Practical computers have a memory hierarchy, where layers of smaller capacity have faster response times, as the speed of light implies. Registers are its very apex. In base 32-bit RISC-V, alias RV32I, there are 32 32-bit registers, named x0 through x31. x0 is special: reading it returns 0 and writing to it does nothing. Reading other registers just returns the last written value. So the first instruction writes to x6.

The other new field is imm[31:12], which stands for the highest 20 bits of the immediate. Thus why the instruction is called Load Upper Immedate: it writes the upper part of rd with bits that are immediately there in the instruction. The lower 12 are set to zero, what if we want something else there?

Opcode sharing

There is no delight in owning anything unshared.

– Seneca

The answer lies in the second instruction:

|31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00|

|11 imm 0| rs1 | funct3 | rd | OP-IMM | |

| 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 1|

| 0 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 3 |

The first new field is now funct3, which allows different instructions to share an opcode:

| Opcode | 000 | 001 | 010 | 011 | 100 | 101 | 110 | 111 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OP-IMM | ADDI | SLLI | SLTI | SLTIU | XORI | SRLI/SRAI | ORI | ANDI |

| OP | ADD/SUB | SLI | SLT | SLTU | XOR | SRL/SRA | OR | AND |

| BRANCH | BEQ | BNE | BLT | BGE | BLTU | BGEU | ||

| LOAD | LB | LH | LW | LBU | LHU | |||

| STORE | SB | SH | SW | |||||

| JALR | JALR | |||||||

| MISC-MEM | FENCE | |||||||

| SYSTEM | ECALL/EBREAK |

Those right of / are chosen by setting to 1 bit 30, except for EBREAK which sets bit 20. With LUI, AUIPC, and JAL these are the 40 base RISC-V instructions.

In this case 0b000 chooses ADDI: Add Immediate among several Integer Register-Immediate Instructions (OP-IMM). Unsurprisingly, it adds the sign-extended immediate to rs1 (source register 1) and writes the result to rd (destination register). Because rs1 is x0, it effectively loads a lower immediate. This is often combined with LUI to load a full register, but here it just loads 0x48 into x5.

Memory-mapped I/O

Memory is the treasury and guardian of all things.

– Cicero

32 registers is not nearly enough of a playground, so RV32I provides an address space of 232 bytes, some3 of which can be read into registers with LOAD instructions and written from them with STORE, as shown by our third instruction:

|31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00|

|11 imm 5| rs2 | rs1 | funct3 | 4 imm 0| STORE | |

| 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1|

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

funct3 being 0 means SB Store Byte. So just the lowest byte from the contents of rs2 (here x5) is written at a memory address calculated as rs1 (here x6) plus an immediate offset (here 0).

The address 0x1000_0000 at x6, loaded by the previous LUI, happens to be connected to the output of the UART in the memory map of the virt machine. And the 0x48 stored by the ADDI is just H in ASCII. The repeated columns in EEPROM.bin become clear: new letters are loaded from immediates into x5 and STOREd to be printed, and the last instruction essentially halts.

This is how, armed with patience, QEMU docs and the RISC-V spec, you too could have written Hello, World! from RISC-V scratch.

-

100 Hz is 6000 RPM, good luck. ↩︎

-

Longer instructions have been proposed but not ratified. ↩︎

-

The memory map of a particular machine defines which addresses map to main memory and which map to other Input/Output devices. The rest are vacant and thus illegal to access (you get a Load Access Fault, which we’ll learn to handle later). ↩︎